Tre Kronor Castle

Tre Kronor Castle

For mankind daunting questions have long baffled us. Who are we? Why are we here? What happens after life? And where did we come from? We try to answer the formed questions through religion, philosophy, and science. And we try to answer the latter question, ‘Where did we come from?’ through genealogy, at least as far as is possible. And we then try to preserve and share our findings for present and future generations, almost bringing back to life those who have come before us. For us with Swedish roots, the history of Swedish genealogy is a long one, stretching far back into the mists of antiquity more than 1,000 years.

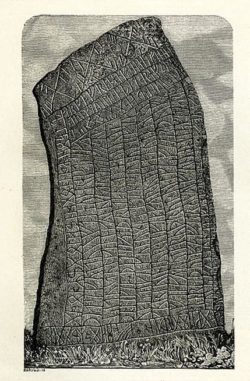

The earliest concrete Swedish genealogical information that comes to us is literally set in stone. This consists of names and relationships inscribed on the numerous rune stones scattered around Sweden and other places visited by Vikings and pre-Vikings. Of some 3,000 surviving Viking and pre-Viking runestones, about 2,500 are found in Sweden, with half of them in Uppland. Södermanland, with some 400 rune stones, has Sweden’s second largest concentration. These rune stones date roughly from 300 A.D. to 1100 A. D., including from the pre-Viking Vendel era, with the largest number being from the late Viking era from about 950 to 1100 A. D. Most rune stones were dedicated to men and erected by their widows, sons, and daughters, and may have marked out territory, a grave site, or event site, or glorified some deceased ancestor or his exploits.

On these rune stones are found Old Norse names, almost all of pagan origin. Some of the runestones depict two or three generations of people, and some of the runestones are connected to yet other runestones and to additional related people. These runestones depict isolated snippets of genealogical information that can not be documented to connect to anyone later in time. Despite the fact that some genealogists have inserted the inscribed people into the earliest generations of their ancestral charts, the evidence simply does not support it. At best, the runic names are but names common to that era, or perhaps found in an ancestor’s local area, albeit centuries removed.

Written by John von Walter Published with permission from Swedish Genealogical Society of Minnesota Originally published in their newsletter Tidningen.

1877 illustration of Rök Runestone 2

1877 illustration of Rök Runestone 2 The Norwegian Eddas, or poems, provide some of the earliest genealogical information on a few of the earliest known Swedish families. Of these Eddas, perhaps the most important is the Ynglingatal or Yngling Saga. It was written in the late 9th Century A. D., probably by Thjodorf, a poet for King Harald Fairhair (ca. 850-932), a Viking regarded as the first King of Norway. It was written to show descent of a Norwegian royal family from the Swedish royal Yngling dynasty from the Uppland area. The work is largely mythical, but partly historical, featuring some 27 early Swedish kings by name, including their death details and burial places. Among the Yngling dynasty those certainly known are Swedish kings Erik Segersäll (ca. 945-995) and Olof Skötkonung (980-1022).

Another very early source of Swedish genealogical data is to be found in the Icelandic sagas, one of the most remarkable medieval histories of Europe. Although the sagas were not recorded until about the 13th Century, scholars believe they were based on earlier oral or written traditions, with most saga events taking place during the period 930-1030 A. D. Authorship for the sagas and their later recorders are virtually unknown, but Snorri Sturluson (1179-1241), who visited Sweden, is regarded as the foremost saga recorder, writing on the lives of early Scandinavian history and kings. The Icelandic sagas, sometimes called family sagas, are prose narratives, largely based on historical events that primarily took place in Iceland from the 9th to the early 11th centuries. They focus on history, especially genealogical and family history, and provide much information on the foremost Swedish families of the same era, even though there are errors and contradictions about what is myth and what is historical fact.

During much of the 1600s Sweden and Denmark were at war with each other. This war was even carried into battles over history and culture. In 1682 both countries sent delegations to Iceland to purchase as many of the Icelandic sagas as possible. Sweden returned with a cargo of them. But sadly, the Danish cargo is gone to history, its ship lost at sea. And with it went what might have been half of the sagas and answers to a great many questions, and much more genealogical information.

“Eddas….largely mythical, but partly historical, featuring some 27 early Swedish kings by name, including their death details and burial places.”

The nobility of Sweden and its once-held duchy of Finland are more than 700 years old, officially dating to about September 1280 and the Alsnö Stadga, a law decreed by Swedish King Magnus Ladulås that defined and put into writing what had probably been practice for some time The Alsnö Stadga formally created a social class with higher legal tax exempt status than that held by commoners, this in return for the pledge of military service to the king. In return, those pledging service were granted exemption from royal taxes on their land, and given frälse status, frälse being Sweden’s early term for nobility. Tax free frälse status enabled Sweden’s privileged nobility to grow wealth and to have the means to buy more land. Nobility became hereditary so that all children of nobles were nobles by birthright.

But nobility could be passed only through the male children. While a daughter was noble in her own right, her children were noble only if she married another noble and had legitimate children. If a noble woman married a commoner her hereditary lands reverted to taxable property, creating a situation where noble daughters most often married noble men, both to retain tax free land and to accumulate larger tax-free estates.

During the Middle Ages and the rise of Christianity in Sweden many nobles donated lands to the church so that produce from them could feed the poor, sustain the church, and build churches and monasteries. In hopes of saving their souls, especially during the Black Death plague of the mid 14th Century, nobles willed or donated lands in great quantity to the Catholic Church. After Gustav Vasa became King of Sweden in the 1500s he set about abolishing the Catholic Church in Sweden, closing its monasteries and confiscating church lands and property.

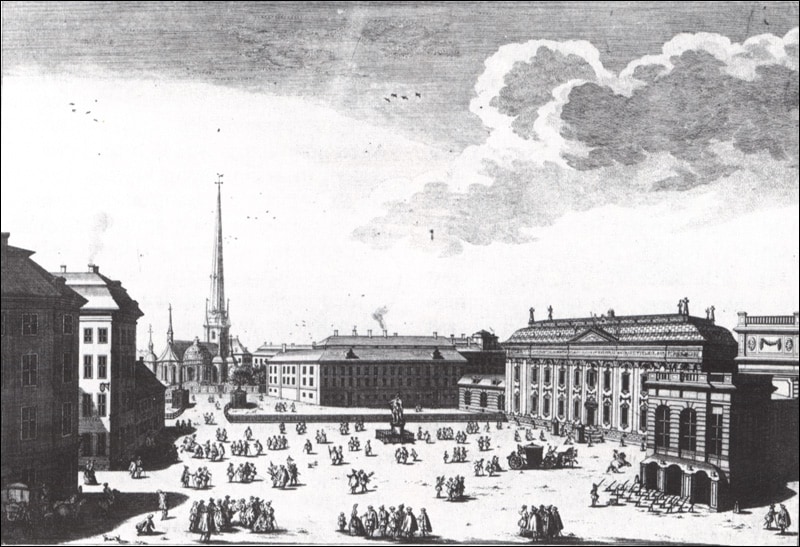

Riddarhuset or Swedish House of Nobility—Photo by Ankara used under CC BY-SA 3.0

Riddarhuset or Swedish House of Nobility—Photo by Ankara used under CC BY-SA 3.0

Nobles protested that certain confiscated church lands should revert to the original donor families, not to the crown, as their ancestors had intended that donated lands go to the church. In the 1540s Gustav Vasa enlisted Rasmus Ludvigsson (1510-1594) to sort it out. Ludvigsson poured through church, monastery donation documents, and epitaphs, and served during the reigns of King Gustav and his sons, Kings Erik XIV, and Johan III. His work with medieval documents compiled data on Sweden’s frälse/noble families and their hereditary lines and lands, leading to the nation’s first formally compiled genealogies, and gave Rasmus Ludvigsson the moniker of “Sweden’s First Genealogist”. Ludvigsson’s original work was lost with the burning of Stockholm Tre Kronor Castle on May 7, 1697, a tragic day for us genealogists, for the entire Swedish royal library and two thirds of Sweden’s nation archives were lost.

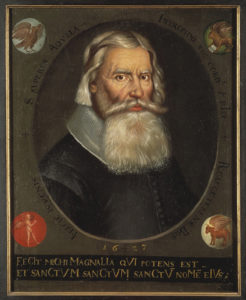

Fortunately some copies of Ludvigsson’s genealogies survived in other collections. Ludvigsson was succeeded by Per Månsson Utter (1566-1623), who became the first royal secretary in the Riksarkivet (Swedish National Archives), which was established in 1618. Utter is regarded as one of Sweden’s early competent genealogists, with some of his greatest works surviving in Collectanea Genealogica in the Riksarkivet.

Utter died of the plague in 1623 and three years later, in 1626, the Swedish House of Nobility (Sveriges Riddarhuset) was created. Here many of the patents of nobility and noble genealogies began to be collected and stored. A grand Riddarhus building was erected between 1641 and 1674 on Riddarholm (literally Knight’s Island), across a bridge from Gamla Stan, Stockholm’s old town. The building survives to the present (shown below) and today contains a fantastic library and archive pertaining to the nobility, genealogy, and Sweden’s history. It also contains many genealogical works on the nobility of other European nations. The Riddarhus today employs a chief genealogist who maintains and updates the ongoing genealogies of Sweden’s noble families.

Written in the first decade of the 1600s, one of the most remarkable early Swedish genealogies is that of Johan Bure, also called Johannes Bureaus (1568-1652). Entitled Om bura namn och ätt, or commonly Johan Bure’s släktbok, it survives with copies in the Swedish National Archives (Riksarkivet) and at Uppsala University in Sweden (numbered X36 and X37). A later version, Johan Bures släktbok i autograph (1613), is in the Armfeltska Arkive of the Finnish National Archives.

Bure’s work is not only remarkable for its early date, but in that it contains genealogies of the common people, including female lines. The genealogy traces back to a certain Gamle (Old) Olof from Bureå Village in Skellefteå Parish in Västerbotten, Sweden who lived in the late 1300s or early 1400s. Recent DNA testing has verified the accuracy of Bure’s work back to Gamle Olof on several of the lines. Today untold thousands can claim to be the descendants of Bure (Bureättlingar), including no less than five of us in SGSM.

Johan Bure’s genealogy actually goes back much further in time, but any earlier generations must be regarded in the nonhistoric and saga category. A later ca. 1740 compilation by Nils Burman is updated and based on Bure’s work and called Bure-ätten, also known as Burman KB1. His handwritten pedigree chart is found in the Swedish Royal Library (Kungliga Biblioteket), Stockholm, Sweden. A good overview on the Bure Genealogy (in Swedish) can be found at: http://familjenbostrom.se/genealogi/bure/.

Another published source for the genealogies of many Swedish-Finnish families in Finland is the Genealogia Sursilliana, first published in 1850 in Swedish by priest Elias Robert Alcenius. The work was started in the mid-1600s by Johannes Elai Terserus (1605-1678), who was the Bishop of Åbo, Finland (and two times my ancestor). Terserus is regarded as the father of Finnish genealogy and as one of the earliest compilers of non-noble genealogies in the Swedish kingdom.

During his years in Finland Terserus noticed that many of Finland’s priest families in Österbotten along the Baltic Sea across from Sweden were related to each other and had common descent from Erik Ångerman Sursill, who was born in the late 1400s/early 1500s in Ångermanland, Sweden. Bishop Terserus began compiling the genealogies of Sursill’s descendants through some 12 female lines, while working with the parish priests in his diocese. Over the next 200 years other priests in Finland continued adding to Terserus’ work. A facsimile reprint of Genealogia Sursilliana was printed in 1960, which includes some 14 generations of descendants in some 400 families. The work was reprinted in Finnish in 1971 under the title Sursillin Suku. In 1981 the work was updated by the Kone Foundation. By one estimate half of all Finlanders descend from Erik Angerman Sursill, testifying to the power of multiplication over five centuries, and to the recording of genealogical records. Sursill descendants can even be found in Sweden, America, and other countries.

Working with Riddarhus material, from 1731 to 1851, a Matrikel öfver Sveriges Rikes Ridderskap och Adel was published by various authors. These contain the genealogical biographies and family circumstances of those initially ennobled and enrolled in the Riddarhus, compiled in order of date of ennobling by assigned chronological numbers. The earliest of these volumes can be found in entirety in Google Books online.

Beginning with the nobility in the 1850s Swedish genealogy was ushered into the modern era. Gabriel Anrep (1821-1907) began privately publishing Sveriges Riddarskap och adelskalendar (Sweden’s Knighthood and Nobility Yearbook), which worked to keep up with noble births, deaths, and marriages while documenting and publishing genealogical descendants of its noble families in alphabetical order.

The series was first published by Gabriel Anrep in 1854, and Anrep was its editor for 50 years until the 1904 edition. The series was issued without major changes until the 1898 edition, but in 1899 when the competing Sveriges Adelskalender was issued, Anrep was forced to amend his series by going annually and adding coats of arms and other graphics to the publication.

Per Månsson Utter (1566–1623)

Per Månsson Utter (1566–1623)  Johan Bure (1568–1652)

Johan Bure (1568–1652)  Bure’s 1613 Släktbok I autograph Photo: Finska Riksarkivet under CC BY-SA 3.0

Bure’s 1613 Släktbok I autograph Photo: Finska Riksarkivet under CC BY-SA 3.0  Johannes Elai Terserus IV (1605–1678)

Johannes Elai Terserus IV (1605–1678)

Over the years it sometimes came out every year,sometimes every two years, and sometimes every three. From 1904-1917 the series continued under Count Adam Lewenhaupt, from 1918-1938 by Count Claes Lewenhaupt and from 1939-1948 by Gustaf Elgenstierna. After Elgenstierna’s death the series ceased to be a private publishing project and was taken over by Riddarhus itself. It is now published every three years.

But Gabriel Anrep is best known for his 4-volume set of Svenska adelns ättar-taflor, a history of the Swedish nobility in genealogical tables, published from 1858-1864. This was Sweden’s first scholarly genealogical work, although it lacks an index and has been given a bad rap for including errors and some fanciful and pompous genealogies, which sometimes traced back to runestones and ancient connections to early royalty. Part of the bad rap is not entiely on Anrep. For permission to use the Riddarhus archives, it was a prerequisite that he must include many of the mythical portions of the noble genealogies. Anrep’s Svenska adelns ättar-taflor can today be found in entirety online on the Internet Archive and Project Runeberg.

A follow up work is Svenska adelns ättar-taflor ifrån år 1857, published in 1897 and 1900 in two volumes with an index, was authored by F. U. Wrangel och Otto Bergström. This brings forward many noble families after 1857 and even includes a much needed index to Gabriel Anrep’s 4-volume set. It does not, however, cover extinct lines or entire family genealogies.

Following up on the previous two works was Den introducerade svenska adelns ättartavlor, Volumes I-IX (1925-1936) by Gustaf Elgenstierna. This monumental set is perhaps Sweden’s largest and most important historical and genealogical work. It is the standard work on Swedish noble families, featuring genealogical tables, dates and places, biographical information, an excellent index that includes patronymics, and many non-noble people connected to noble families.

This set is available, but not for loan, at the Wilson Library, University of of Minnesota in Minneapolis, the Memorial Library, University of of Wisconsin in Madison, the University of Washington Library in Seattle, the Swenson Center at Augustana College in Rock Island, Illinois, the American Swedish Historical Museum in Philadephia, Pennsylvania, and perhaps other locations.

A facsimile sets of nine volumes, now sold out, was published in 1998 by Sveriges Släktforskarförbund (Sweden’s Federation of Genealogical Societies). Each of the nine volumes is 700-800 pages in length and contains Swedish living and extinct noble families introduced in the Riddarhus (House of Nobility). The families are presented alphabetically in genealogical tables.

In Volume IX are additions, corrections, and a 470-page index which includes many non-noble people through marriages, often including even their parents. And in many cases non-noble individuals are listed as forebears, who some time later had a descendant who was ennobled. Anyone working back their genealogies should take a lookmat the index. The Riddarhus has digitized the entire work, including two supplemental volumes from 2008 with new information and corrections, but ongoing discussions about making them available online have not yet produced results.

In 1979 and 1880 Oskar Wasastierna published a similar work in two volumes covering Finland’s nobility, entitled Ättar-taflor öfver den på Finlands riddarhus introducerade adeln Volume I, A-K (1879) and Volume II, L-Ö (1880). This work can be acessed online by Googling the title. Swedish noble families survive in great numbers in Finland, which for some 600 hundred years was a part of the Kingdom of Sweden. At various times Finland was called a called a duchy or Grand Duchy of Sweden (under a duke or other member of the Swedish royal family), until it was transferred to Russia in 1809, a result of the the Napoleonic Wars.

Gustaf Elgenstierna

Gustaf Elgenstierna After 1809 Finland created its own House of Nobility and parliament, laid out largely on the Swedish model, and grandfathering in Swedish noble lines living in Finland, while adding some Russian nobles created under the Tsars. The Finnish Riddarhus website is found at: http://www.ritarihuone.fi/svenska/riddarhuset/.

Many Finnish noble families are also represented in the Swedish Riddarhus. From 1937-1954 Tor Carpelan updated Wasastierna’s work with his Ättartavlor för de på Finlands Riddarhus inskrivna ätterna, written in English and found at some of the better libraries. Tor Carpelans Finnish nobility works, called Ättartavlor, include a register of Finnish and Swedish-Finnish Noble families with genealogies in three alphabetical volumes, with a supplemental index. They are entitled Ättartavlor II, A-G [1954], Ättartavlor III, H-R [1958], Ättartavlor IV, S-Ö [1965].

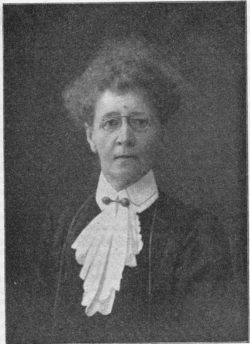

Frälsesläkter i Finland intill Stora ofreden (1909), is a landmark work authored by Jully Ramsey (1865-1919), who was one of the first females of renown in the field of genealogy. Her work covers Finnish-Swedish and Finnish frälse/pre-noble genealogies up to about 1720, with many from medieval times. Jully Ramsay’s work is online at: http://runeberg.org/frfinl/.

Another fine work covering many medieval and early families in the Swedish Kingdom is Äldre svenska frälsesläkter. It was written by several scholary authors and published by Sveriges Riddarhus. Its manuscripts contain genealogies of Swedish and Finnish early and medieval noble families which had died out the male line before the Riddarhus was created in 1626.

Part I was published in three parts: 1957, 1965, and 1989. Part II was published in its first part in 2002. Part III was published in 2013 and contains the index to all five All five soft-cover parts are available for purchase from Sveriges Riddarhus for about 1200 Swedish kronor. An index to the genelogies printed to date, plus a list of those to be published in the future is found at: sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Äldre_svenska_frälsesläkter.

For those researching clergy ancestors there are many printed works documenting the biographies and genealogies of the Swedish priests and chaplains, both from the Catholic and Lutheran eras. Such a work is called a herdaminne (herdaminnen when plural), and there may have been one or more historical works or revisions for most of the dioceses (stifts) in Sweden, Finland, and Sweden’s historical possessions. These herdaminnen began to be compiled in the 1700s and continue yet today. They are scholarly works, usually containing information from the Middle Ages until the date of the work’s publication, and are unique in the world to Sweden and Finland. Most of them have a section on the church history of each parish in the diocese, followed by chronological biographies of the priests and chaplains.

The best herdaminne for each diocese (usually the most recently published) often includes much detailed genealogical material, such as birth dates and places, parents’ names, death dates and places, burial places, career history, marriage dates and places, wife’s parents and her birth and death data.Similar data can also be found for the couple’s children. Biographical data on the clergyman may include education, previous church service, writings, censures for behavior, unique life events, church and priest estate inventories during their tenure, etc. If one has a priest-ancestor often their genealogies can be followed in one or in various parishes of the same diocese. And at other times they can be followed in various parishes and dioceses in other herdaminnen.

Tor Carpelan (1867–1960)

Tor Carpelan (1867–1960)  Jully Ramsay (1865–1919)

Jully Ramsay (1865–1919) “An important leap forward in Swedish genealogy came in 1885 when archivist Viktor Örnberg (1839-1908) began publishing his groundbreaking work of non-noble genealogical and biographical works on Swedish families having non-patronymic surnames.”

A list of the Swedish and Swedish-related herdaminnen (including for Finland and Sweden’s historic Baltic possessions) website can be accessed at: http://sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herdaminne, given in Swedish, but translatable to English on the Internet. Acheck of the world library catalogue will show which libraries hold the selected editions. While many libraries hold them as only reference works, some libraries will let them out on interlibrary loan.

In the Midwest, the Wilson Library at the University of Minnesota and Memorial Library at the Univerity of Wisconsin both hold some of the herdaminnen. The Swenson Center at Augustana College in Rock Island, Illinois also holds many of Sweden’s herdaminnen. Google has just started putting some of the herdaminnen on the Internet in entirety, and some are accessible through other sites, for example, the Hernösands stifts herdiminne, found at http://www.solace.miun.se/~blasta/herdamin/.

In the 1800s we began to see a few compiled genealogies for local areas and towns, a process which continues today with many local hembygdsförengar (local historical societies) and local genealogy groups. An early Swedish example came in 1853 when historian Karl Gustaf Kröningssvärd (1786-1859) published his Genealogiska Tabeller, also called the Diplomatarium Dalecarlicum, featuring the genelogies of many of Dalarna’s medieval frälse and noble families.

It may be found at a few of the better libraries, including the University of Minnesota’s Wilson Library. Based on parchment documents, the work, however, contains a number of errors based on false conclusions.

About 1830, Erik Sehlberg (1794-1842) composed his Gefle och dess slägter under 1600- och 1700-talen, which compiled many family genealogies from the 17th and 18th Centuries in the town of Gävle in Gävleborg, Sweden. Copies of his work can be found in the Gävle Stadsbibliotek (city library) and in the Kungliga Biblioteket (Swedish Royal Library) in Stockholm, Sweden. In 1890 Tor Carpelan (1867-1960) published Åbo i genealogiskt hänseende på 1600- och början av 1700- talet, and about the same time Köpman släkter i Åbo på 1600 och 1700-talen, both works on the genealogies of the burgher and merchant families of Åbo, then the capital of the Swedish Grand Duchy of Finland. Carpelan’s latter work can be found in the library archives of the American Swedish Institute in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

An important leap forward in Swedish genealogy came in 1885 when archivist Viktor Örnberg (1839-1908) began publishing his groundbreaking work of non-noble genealogical and biographical works on Swedish families having non-patronymic surnames. Today it includes more than 2800 Swedish families and has been published continually from 1885 to the present, though not in every year. The publisher today is Föreningen Svenska Släktkalendern, a nonprofit organization.

The work was first published as Svensk Slägtkalender from 1885–1888 och then as Svenska ättartal from 1889–1908. The early years of the work are often popularly labeled as just Örnberg’s ättartal. Since 1912 it has been published under the name Svenska Släktkalendern. The series can be found on loan from the LDS library, and is available online via an ArchiveDigital subscription. Here is a link to an index of families that have been published in the work, current up until 2014: http://www.svenskaslaktkalendern.se/sskreg.html.

A fine Swedish-language periodical that carries much genealogical and biographical material is Svenska Autografsällskapets Tidskrift, which was published from 1879-1897, then by the Svenska Autografsällskapet from 1898-1905, and finally by the Personhistorisk Samfundet as Personhistorisk tidskrift from 1906 to the present. These are available in the U. S. in some of the better libraries’ periodical collections, and by loan through the LDS libraries. An index to Personhistorisk tidskrift articles is online at: https://www.abc.se/~m225/litteratur/artpht.html .

Two similar landmark periodicals published in Swedish that contain Finnish genealogical information and available at a few better libraries are Historisk tidskrift för Finland (HTF), which has been published four times per year since 1916, and Genos, published usually four times per year by the Genealogiska Samfundet i Finland. Back issues can be purchased for Genos, and an index to Genos-covered families can be found at: http://www.genealogia.fi/genos-old/indexr.htm. Both publications are probably also available by loan through the LDS libraries.

A more recent Swedish language periodical is Slaktoch Havd, an historical and genealogical publication printed in Sweden by Genealogisk Föreningen from 1950 to the present with 3 to 4 issues per year. It has an online index to all articles and well as a family name search engine: www.genealogi.net/innehallsforteckning-for-slakt-ochhavd-1950-1959/.

Many of us doing genealogy in America are perhaps unfamiliar with most or all of the foregoing works, books, genealogies, and periodicals written from the 1500s to the mid-1900s. But despite their early dates they are loaded with historical, biographical, and genealogical information, and are amazingly accurate to the present. And in many cases you can find no better information on your earliest ancestors.

Despite the fact that all are in Swedish you’d be surprised how much you can understand with a Swedish-English dictionary and Google Translate. And with a little work some of these works can be found to be available at various world libraries, including in the U.S., but usually available only in the reference section and not let out on loan. Photocopies must be ordered, or one must visit the library. Check the world catalog at your local library for locations, or contact the LDS, which has most of them.

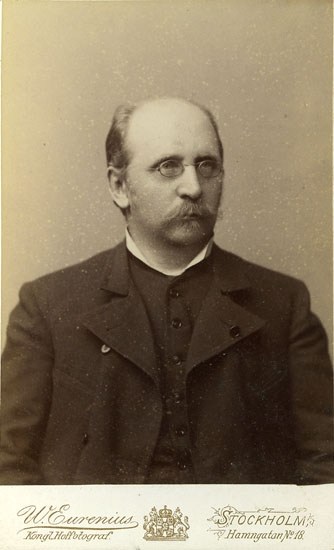

Viktor Örnberg (1839–1908)

Viktor Örnberg (1839–1908) “But things were to get even easier for us genealogists. No longer do we need to order, wait, and then have to reorder and again wait when ancestors changed parishes.”

The Swedish Church Laws of the 1600s began creating many of the records we use in today’s genealogy. But they were long not available outside of Sweden. In 1894 the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints began dedicating time and resources to collecting and sharing genealogical records, and beginning with photography in the 1940s, the Mormons began microfilming Swedish records. And since 2006 they have began copying them digitally, with all available on loan through LDS libraries. In Sweden SVAR (short for Svensk Arkivinformation) which contains Sweden’s National Archives, digital archives, indexes, and databases were first microfilmed, later digitalized, and available for purchase on microfiche. Their online index: https://sok.riksarkivet.se/specialsok.

But things were to get even easier for us genealogists. No longer do we need to order, wait, and then have to reorder and again wait when ancestors changed parishes. Genline digitized the Swedish archives, including church records, and made them available online in our homes by subscription, before the company was merged into Ancestry. And ArkivDigital is today the largest private provider of Swedish church and historical records online.

ArkivDigital has clearly photographed images of the original documents. It includes some 67 million color images covering historical documents such as church, military, probate, and court records, and more. And it’s available online in our homes with a paid subscription: http://www.arkivdigital.net/.

Rötter’s Anbytarforum, is a wonderful cost-free online forum site operated by Sveriges Släktforskarförbund (Sweden’s national federation of genealogical societies), which provides for questions and answers, a surname list, parish and regional lists, lists of Sweden’s area and local genealogical societies, and a great many other varied resources. Most of it is in Swedish, but there is much also in English. It’s website is: http://forum.genealogi.se/.

Today, genealogy has come to a new frontier, DNA genealogy, with several companies providing testing and showing our ethnicity percentages and genetic matches to others, all for proscribed fees. Among them are AncestryDNA, Family TreeDNA, 23 and Me DNA, GEDmatch, with more cropping up. And for those on Facebook a forum group called DNA-anor has daily cost free articles, information, and question and answers, and the latest DNA news.