Written by Giles C. Ekola, The Finnish American Reporter, Oct. 1998.

Submitted to SFHS by June Pelo.

Images updated to meet attribution standards in 2021.

The creativity of the Finns is recognized in areas such as architecture, literature, music and technologies. This article focuses on six historical leaders who developed the Finnish language and national identity. A common language provides the means for populations to achieve a national unity and culture. Without the foresight and creativity of these six, there may never have been a Finnish nation.

Every independent nation has scores of men and women whose thought, creations and deeds have made possible their country’s nationhood. In America we have Thomas Paine and Francis Hopkinson. Paine wrote his fifty-page booklet, Common Sense, which stirred the colonists to act. Hopkinson designed the American Flag, our symbol of unity. Both still help us to understand [and] define our country.

Finland’s freedom and independence could neither be conceived nor achieved in the brief span of time as that of America. Sweden’s forced annexation of Finland began around 1200. Its rule lasted more than six centuries. In 1807 Napoleon plotted with Tsar Alexander I to convince Sweden to help in their war against England. They failed. Russia then attacked Finland and Sweden in 1808 and won the war, fought largely by the Finns, in 1809. Finland was made a Grand Duchy of Russia. Russia’s rule, ranging between benevolent to despotic, lasted more than a century.

People under foreign control for centuries see it as unchangeable. But certain people in Finland worked with the elements of national identity in both the Swedish and Russian periods.

MICHAEL AGRICOLA (1510-1557)

1910 recast of Michael Agricola in the Turku Cathedral.

Attribution: Markus Koljonen, CC BY-SA 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ , via Wikimedia Commons

Finnish has a long history as a spoken language. Michael Agricola developed it into written form and systemic use. Born in 1510, he grew to manhood with two driving causes in mind, Christian faith and the Finnish people. As a gifted student he was sent to Wittenberg, Germany, to study under Martin Luther and his co-worker, Phillip Melanchthon.

In 1531 Agricola returned to Finland. He was assigned to the cathedral school in Turku where he taught pastoral candidates biblical studies, theology and the duties of pastors. He had a major influence on the people of Finland by virtue of his personal dedication. What he did for the Finnish language outreaches his lifetime of service.

During time away from classrooms and pastoral work, Agricola gathered the letters of spoken Finnish into an alphabet and a study book called an aapinen. He translated the catechism received from Martin Luther. He prepared a prayer book in Finnish. Later he translated the New Testament and much of the Old Testament. People were drawn to them for their content and the Finnish language.

Agricola is recognized as father of the written Finnish language. His objectives were to foster and nurture the faith and to help people to learn and grow.

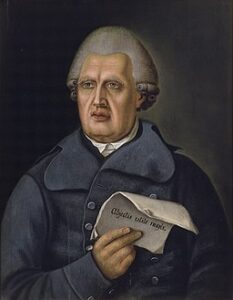

HENRIK PORTHAN (1739 – 1803)

Attribution: Johan Erik Hedberg (1767–1823), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

After Michael Agricola many people could be named for their contributions to the Finnish people, but a history teacher comes into our view for the creative intensity of his research, teaching and ideas. He is Henrik Porthan who taught at the University of Turku. He died 24 years before the university burned and was moved to Helsinki. Following his death students and scholars formed a Saturday Society to study and discuss his ideas. He taught in the 18th century but his largest impact came through the Saturday Society in the following century.

What was it about Henrik Porthan that caused people to take up his legacies? What he found in the history of the Finnish people helped him to envision what they could accomplish, what they could become. What he learned through his research he taught and articulated well. For these reasons Henrik Porthan is every bit as creative of the Finnish identity and culture as those who followed him.

JOHAN LUDVIG RUNEBERG (1804 – 1877)

The son of Finland who brought his country some of her earliest literary and intellectual acclaim was Johan Ludvig Runeberg. He was born in February 1804 and raised by an uncle due to the poverty of his parents who had younger children to house, clothe and feed. Being gifted he tutored children of wealthy families for a living and later for his studies at the University of Turku. He learned of Professor Henrik Porthan and joined others in their study of his ideals. He earned his doctor of philosophy degree in 1827 shortly before Turku and its university were claimed by fire.

By 1830 he had published a book of poems, translated and published another and also began a periodical called The Helsingfors Morgonblad. While Runeberg wrote and published in Swedish, his life and thought were centered in Finland. Except for one short trip to Sweden, Runeberg lived his entire life in Finland. Despite this he came to be recognized as one of the leading poets and thinkers of all Scandinavia.

Runeberg published a number of books such as Kung Fjalar in 1844. The same year the King of Sweden decorated him with the Order of the North Star. Most noteworthy of his books was The Songs of Ensign Stål. It deals with the war against the invading Russians in 1808-1809. Finnish heroism and pride occurs and reoccurs in Runeberg’s book of vivid poems.

Runeberg reached his beloved countrymen. A further bonding with them was forged when the book’s poem of dedication, “Our Land,” became Finland’s national anthem.

DR. ELILAS LÖNNROT (1802 – 1884)

What drove this doctor of medicine to seek, sort out and publish the sung legends and poems of the folk and peasants of Finland and Karelia? What excited him to do this? What gave him the determination and stamina to stick to his task?

Born in 1802 into the family of a village tailor he spent work time in his father’s shop. He also worked in an apothecary to earn for his costs at the University of Turku. Others at the university who studied folk poetry sparked his curiosity about the subject. He made Väinämöinen the focus of his master’s thesis. Perhaps the apothecary experience, folk medicine or something from Henrik Porthan’s work contributed to Lönnrot’s interest in medicine. Perhaps he foresaw how he could combine medical calls with literary research. In any case he completed his doctoral studies in 1832 with a study of healing and medicine among the folk and peasant Finns.

Dr. Elias Lönnrot made many trips in Finland and Karelia to gather as much as he could of the legends and verses. Equipped with a flute, writing materials and his doctor’s kit he attended to persons with illness or injury when the need arose; provided music for events of life such as weddings and village gatherings; and responded to rune singers when they were ready to share. He listened to, memorized, sang and recorded dozens of poems and thousands of poem lines.

In 1835, Lönnrot published the first Kalevala in a limited number. In 1849, his enlarged and revised Kalevala was published. By then a waiting readership in Finland and other countries was anxious to secure this epic of Finland. Runeberg and Lönnrot did so much for the identity and culture of their people. It remained for another to make the benefits of their work known and usable in all of Finland.

JOHAN VILHELM SNELLMAN (1806 – 1881)

The third person of the Saturday Society who made major gains for the cause of Finland was Johan Snellman. His contributions built on those of Runeberg and Lönnrot. With them he believed in the quality, strengths and wisdom of the Finnish people. No nation of credible character and purpose would overlook the human resources and potentials in its folk and peasant populations. In them the future of Finland was to be found.

Johan Snellman recognized the need for two considerable changes essential for Finland’s future. First, the education of Finnish speaking children needed to take place in Finnish, not Swedish. Second, the Finnish majority and the Swedo-Finnish minority needed to be reconciled into a cohesive society.

Through his own periodicals, one in Finnish and one in Swedish, Snellman brought the issues to his readership. Snellman kept the Grand Duke of Finland, Tsar Alexander II, informed of developments and the needed changes. Alexander II also knew that Sweden was coveting the now more prosperous Finland.

In 1868 Alexander II issued a Language Edict which made Finnish the language of children’s education in Finnish speaking communities. Swedish was allowed in the schools where Swedish was the local language. Finnish became one of the two languages of Finnish governmental personnel. Government administrators and workers were given twenty years to become proficient in Finnish.

Johan Vilhelm Snellman is one of the persons whose creative passions freed the Finnish language from its historical shackles and helped to bring the Finns and Swedo-Finns together for the sake of their country.

ALEKSIS KIVI (1834 – 1872)

From the province of Häme came a man of incomparable gifts of language. His powers of observation, human characterizations and drama, coupled with his superb language skills, won him Finland’s highest literary acclaim. His name is Aleksis Kivi.

Kivi was born beyond the time that would allow him to have participated in the Saturday Society’s probing discussions of Henry Porthan’s work. But Kivi’s instinctive, driving interest in his fellow Finns brought him into that company of people who believed in the future of Finland.

Kivi wrote as a dramatist and novelist. Plays he did for the theater are Lea and Village Cobblers. Their performances mark the beginnings of Finnish theater, an undertaking that was summarily opposed at that time by Swedish speaking citizens. His plays are masterful and their high standings continue.

The greatest work of Kivi is his novel, Seven Brothers. It was published when he was thirty-six years of age. In this work the Finns could read about themselves, see themselves. The realities of life in Häme were before their eyes. The emotions in the novel were theirs. Everything they knew was there, simple but heroic. When Seven Brothers was absorbed by the Finns they took Kivi into their hearts in a way that reflects what he gave to them. They came to love him because he loved them, their way of life and their language.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE SIX

During the 20th century I, as well as others, have heard references to these six men and others by grandparents and other relatives, in church and historical society meetings and later in post high school studies. Memory and curiosity cause us to ask, “What was their significance?” It lies in the use of their creative talents toward the nationhood and independence that their country ultimately achieved.