Being Deaf

- An English translation of an article by Eeva Salmi & Mikko Laakao, Maahan Lampimaan – Suomen Viittomkelsisten Historia (The History of Finnish Sign Language)

- An online story about Carl Oscar Malm at the Finnish Museum of the Deaf http://www.tkm.fi/CO_Malm/malm_main_en.htm

For centuries “deafness was considered to be a punishment from God and the mental skills of deaf people were considered to be both limited and naïve.” A change in that perspective began in the late 1700’s when schools for the deaf were established all over the world. “These schools brought large groups of deaf people together for the first time. The significance of these schools for the deaf community is difficult to overestimate. Sign language of the deaf communities were created and developed within the schools, and the students then further passed on the languages.” Sign language became the tool for communication and learning.

Carl Malm & Deaf Education

Carl Malm also became deaf as the result of a childhood illness. There were no deaf schools in Finland when he was a child. Wanting an education for their son, his parents sent him to a Swedish deaf school in Stockholm in 1834. Carl was eight when he began learning Swedish sign language. He continued studying in Sweden until he graduated in 1845 and moved back home to Borgå. In February of 1846 Carl began working as a private teacher for two deaf boys in the parsonage of Koivisto. In less than a year, he opened a private school for the deaf in his father’s house. That was in October, 1846. Swedish sign language was taught and it was used as the language of instruction. Carl also emphasized the importance of written language. He regarded the written language as a “necessity for the sake of information acquisition (intake) and communication (output) with the hearing.” Carl believed there was a need for deaf instruction in Finland. Despite advertising his deaf school in the newspaper, including that those of all incomes were welcome, his only students were the two boys he tutored the previous year. Carl then asked the Diocesan Chapter of Borgå-Porvoo to find out how many deaf people there were in Finland. “The result of the count in 1848 was that there were 1,466 deaf people in Finland, 602 of whom were under 20 years of age.” He had the numbers to show there was a need for a school for the deaf.

From Sign Language to Oralism

Deaf schools continued after Carl’s death. In the forty-five years between his death and the enrollment of my Great Uncle Edvin at the Borgå Deaf Boarding School, philosophies on deaf education changed. At the end of the 19th century there wasn’t an international sign language, but deaf people who were geographically close used a similar version of signing. Communication increased within deaf populations. Around the same time, during the period of Finnish nationalism, the use of a single language grew to be highly valued. Sign language was seen as an additional, primitive language that would be used to isolate deaf people from being a part of the ‘one voice’ of Finland. Deafness continued to be seen as a disability that required treatment and healing. Rather than teaching sign language, it was believed that deaf people should, and could be taught to talk. And so, there was a shift from teaching sign language and using it to teach academics to teaching how to speak. The term used to describe this new approach was called ‘oralism’ or ‘speech instruction’. Various tools or instruments were used to teach deaf students how to position their throat and mouth so the sounds that came out would sound ‘normal’.

My Discovery of the Borgå Deaf Boarding School

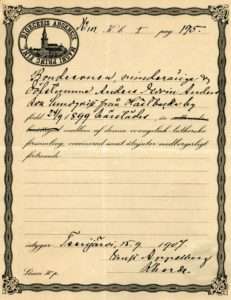

In the late 1970’s my cousin interviewed and videotaped my grandmother for a class project. Before going to Finland in 2019, I watched the video again, hoping to pick up more details about her life. During the interview she said she traveled only twice far from her home in Terjärv; once to visit her brother Edvin in Borgå when he graduated from the deaf boarding school and once when she went by train to Hangö to immigrate to America. I never paid attention to where the boarding school was before planning my visit to Finland. Now I searched for it online. In less than an hour I found it! The school had closed in 1993, but the buildings were in-tact. I also discovered that there was a Finnish Museum of the Deaf in Helsinki. I sent an email to their historian hoping to verify Edvin attended that boarding school. I sent his full name, his parent’s names, his birthday and the parish his family was from. About six weeks later I got confirmation he had attended that school. Attached in the email were five enrollment documents found in their Tampere archives. They were stored along with applications of other students who were accepted at the boarding school in 1907.

Below is a copy of the application my great-grandfather Anders Sundqvist filled out for Edvin.

Pictures courtesy of the Finnish Museum of the Deaf in Tempere

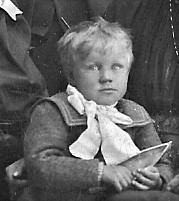

While visiting Tempere, where the school archives are stored, I arranged a meeting with the historian to see the original school application documents. I had previously asked if they had any pictures of Edvin. The historian did not find any with Edvin’s name. During my visit I was allowed to go through a box of unidentified photos. I used two pictures of Edvin to help look for him.

Left to right: older sisters Hildur & Teckla (my grandmother) and Edvin

Left to right: older sisters Hildur & Teckla (my grandmother) and Edvin  Edvin Sundqvist – perhaps on his school graduation

Edvin Sundqvist – perhaps on his school graduation I did not recognize Edvin in any pictures in the school archives, but I found a series of pictures likely taken the last year Edvin would have attended the school, dated January 1914. All school pictures are courtesy of the Finnish Museum of the Deaf in Tempere  Younger students

Younger students  Speech instruction class

Speech instruction class  Older students

Older students

Dining hall

Dining hall  Girls physical education

Girls physical education

Girls sewing class

Girls sewing class

Boys wood working class

Boys wood working class

Two days after looking at the archives, our tour bus made a few block detour so that I could see the Borgå Deaf Boarding School. It looked just like the pictures from 100 years ago. I was elated to see it first hand!