The following was written by Mrs. Sadakichi Bartmann, traveling from New York to Paris, and was published in the Boston Evening Transcript on December 21, 1892. Thank you to June Pelo for discovering this firsthand account. *Editorial note: The woman writing this account is clearly not suffering from the poverty that became the impetus for mass migration. She could buy solutions to any discomfort in steerage that became too much for her. She also shows a clear disdain for fellow steerage passengers. It is unclear if her disdain is caused by racism, classism, or a general distaste for immigrants. What is clear is that she lacked empathy for the diverse collection of immigrants sharing this tough journey. This article, from a modern viewpoint, reads as if she is taking a selfie but the real story is in the background.

I had the means to live economically in Paris for two years while pursuing my studies in an academy of music, but decided to save money by taking passage in the steerage in spite of the protestations of my family. I chose one of the slow steamers because travelers had told me the space allotted in steerage was larger and the treatment was more humane.

When New York was out of sight, the steeragers were driven downstairs in a line to show their tickets to an officer, who tried to suppress all his colleagues in a harsh voice and rough manner. I looked for the head steward and bribed him with a fee to give me as good a berth as possible. I was put into a compartment, a narrow aisle with two rows of beds on either side, originally meant for 24, but now occupied by 12 people, which allowed an empty berth to stow one’s baggage. An upper berth was my lot, in one of the corners near the window, so I was protected at least on one side. My neighbor was a half-crazy German woman, with exceedingly dirty habits and unkempt appearance; she had a weakness for using her lap as a dish for sauerkraut, potatoes and herring during meals, offering me an assortment of eatables she had brought with her. The rest of the beds were occupied by women and two married couples. I did not find the presence of the men very appropriate, although they behaved respectably. But these are the small annoyances attending a cheap trip! Thus the pleasure of giving myself a good washing or of changing my underwear was denied me during the entire voyage.

The food was plentiful and good enough though tasteless, being cooked by steam. “You will have to try and get along with the steerage food,” remarked the steward as he ladled the pea soup out of a huge pail with much splashing, but I could not manage it.

That first night when I climbed up to my bed with its mattress and blanket for which I had paid twice its value, I felt very homesick and wept silently in my squalid surroundings. I was awakened in the night by the loud cries of an Italian woman beneath me. This woman was my special aversion; she surpassed my German neighbor in her unkempt, dirty appearance, and was suspected of harboring vermin. The cause of her cries was a bottle of wine in my berth, which had been carelessly corked and was now spattering down into the bed below. My efforts to explain matters were in vain, because the Italian did not understand a word of English. Some occupants felt sorry for her, while others took my part. Our peaceful neighbors became two hostile camps; there was an exchange of invectives, sarcasm, with the din of crying children, and order was only restored with the intervention of the steward, who was on watch all night.

In the meantime the ship was beginning to rock and groans and sighs told us that our neighbors were feeling seasick. The air was close and foul because the ventilators had to be closed as the sea was splashing in the windows and soaking our beds. At the break of day, I jumped out of bed, and dressed as I was, groped my way on deck. I felt the time had come to pay my tribute to Neptune. The decks were streaming with water, getting their early washing. The stormy sea stretched to the horizon and the dull sky above was steeped in a sickly gray. An officer went by smiling at my appearance: dishevelled hair, shivering in an old wrapper, covered with white flocks from my bed blanket.

Days of misery began for us poor steeragers. The sea beat on the deck, drenching us to the skin, the rain fell in torrents and the ship’s tossing made life unbearable. Seasickness under such conditions is a means of torture. One stands for days in wet shoes and stockings, which cannot dry overnight and have to be donned wet in the morning, our clothes are damp and ill-smelling, from being worn wet and in bed; chilled to the bone and racked with fever, one finds no rest on the hard straw and the short beds. And what with the noise of so many congregated in so small a space and the odor of people who have not changed their clothes for months, without a breath of air in a tightly closed space, one begins to regret the tendency to be economical. It is especially sad to notice the little children; during the stormy weather they crept away from sight, pale and sick, and no joyful word or play enlightened these little mortals; they could not eat food, and dirty and sad they lay about where they could.

Yet all things come to an end, and the bad sea and gray sky were succeeded by calm and sunshine. The girls came out in holiday attire, the children began to play and the windows were opened. Our appetites increased and we began to wonder how we could bribe, coax and induce the officials to give us better food. The steeragers provided with money had food smuggled to them, which was termed “cabin food,” and was actually the food of the lower officials. Twice a day I stole with a tin dish into a certain pantry under the cabin and was served with a large portion of “cabin food” by a little fat jolly cook’s helper as he gravely looked up at the captain who was staring at the horizon. Selling of eatables was prohibited, but as the pastry cook also wished to make money, I was also well provided with cakes and biscuits.

There were no conveniences for dining, so each passenger had to climb into his bed with his food and eat it. Moreover, one has only one plate for soup, meat and dessert, and the knife is so blunt or the meat so tough that the rest of the food spatters over the bedclothes before the tussle is over.

As for climbing into bed I had acquired a proficiency at it and made it in a matter of a second. I stepped on the lower bed, turned swiftly and with a skillful movement lifted myself and landed in the tiny berth. Another disagreeable thing was the washing of the dishes; there being a great deficit of fresh water, one wavered between the alternatives of rinsing them in cold salt water, or of leaving them as they were. In any case the knives were never free from a thick coating of rust.

A thing which will always prove interesting in steerage is the study of the different passengers, about 200 on this trip. Almost every European nationality is represented. There were Poles in gray linen suits with baggy pants and high-heeled topboots; Hungarians with dusky skins, large slouched hats looking like stage brigands; Norwegians in red shirts and fur caps, who had made and lost a fortune in California and returned home as poor as they left; Frenchmen in brown velvet suits who were glad to return to the vineyards of France.

There were Polish Jews, who were dressed entirely in rags, of every shape and description, the majority were old women with beaked noses and witch-like faces, young women fading early, and beautiful large-eyed children. The Italians were very amusing to watch; they lay around on the deck, stretched at full length, huddled against each other under a ragged blanket. They were continually jabbering and quarreling and eating onions. The men of the family were entirely swayed by the old women, and there was generally a wrangling over money. One of them told me that after landing in New York he walked up Broadway, but he had scarcely gone a mile when the traffic and bustle so frightened him that he at once made his way back to the pier and bought a return ticket for the old country. The Italians were absorbed in the game of maro, a rather stupid game, but capable of making them excited and noisy. They seemed quite well provided with money and were merely making a pleasure trip.

The good weather brought another pleasure. The captain ordered the hand-organ to be played, which a little sailor ground away at for hours. Dancing was not very energetic, however. Less delightful was the sailor’s band consisting of a fiddle, a harmonica, a trombone, a drum and two tin lids as cymbals. Strange to say, nobody could make out what tunes they were playing.

By this time my mattress had worn so thin that I felt the iron bars through it and lay awake for whole nights. The steward shrugged his shoulders when I complained, but brought me a new mattress soon after along with hot rolls, with the compliments of the pastry cook.

All our hopes were now centered on the end of the voyage. What pleasure it was to greet the first vessel after a monotonous week of sea and sky. It was a beautiful sight, a full-rigged vessel with its white sails expanded and swayed by strong breezes, rising up and down the waves.

What a sensation the first lighthouse created among the passengers, the “cabin gentlemen and ladies,” affecting a peculiar walk to express their superiority, walked around to inspect the land on the other side. The first day brought beautiful weather and a calm sea; numerous ships, sailing vessels, and fishing smacks covered the waters; steamers bound for America, with their enormous loads of steerage passengers, passed us now and then amid mutual cheering. There was plenty of music, and the liquor flowed extravagantly; the sailors and our good stewards thought it time to begin their sprees, and were very gay and unstable with their legs. Nobody wished to go to bed, and when driven down at last, they busied themselves packing and dressing in spite of being warned by the officer that they would not land before nine the next morning; and for those few who lay quietly in bed, sleep was made impossible.

When the people found at last that it would take several hours before landing, they wanted to have a little more sleep, but to punish them they were all sent on deck, which was being washed. The people crowded together like a flock of sheep in a thunderstorm, trying to find a dry spot. At last we touched the landing place and the bridges were let down. The steeragers were very anxious to reach land and pushed themselves among the cabin passengers, some of whom seemed to begrudge their escaping from their misery as soon as they could.

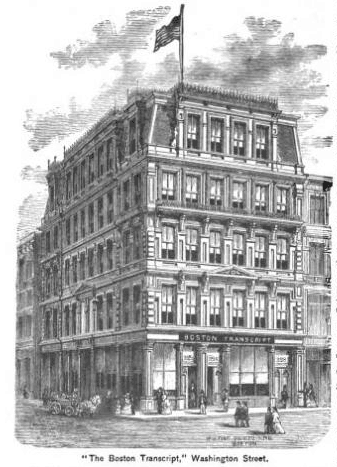

The Boston Evening Transcript ran a genealogy column from 1906–1941 and documented over two million names. Illustration by Moses King, 1872.